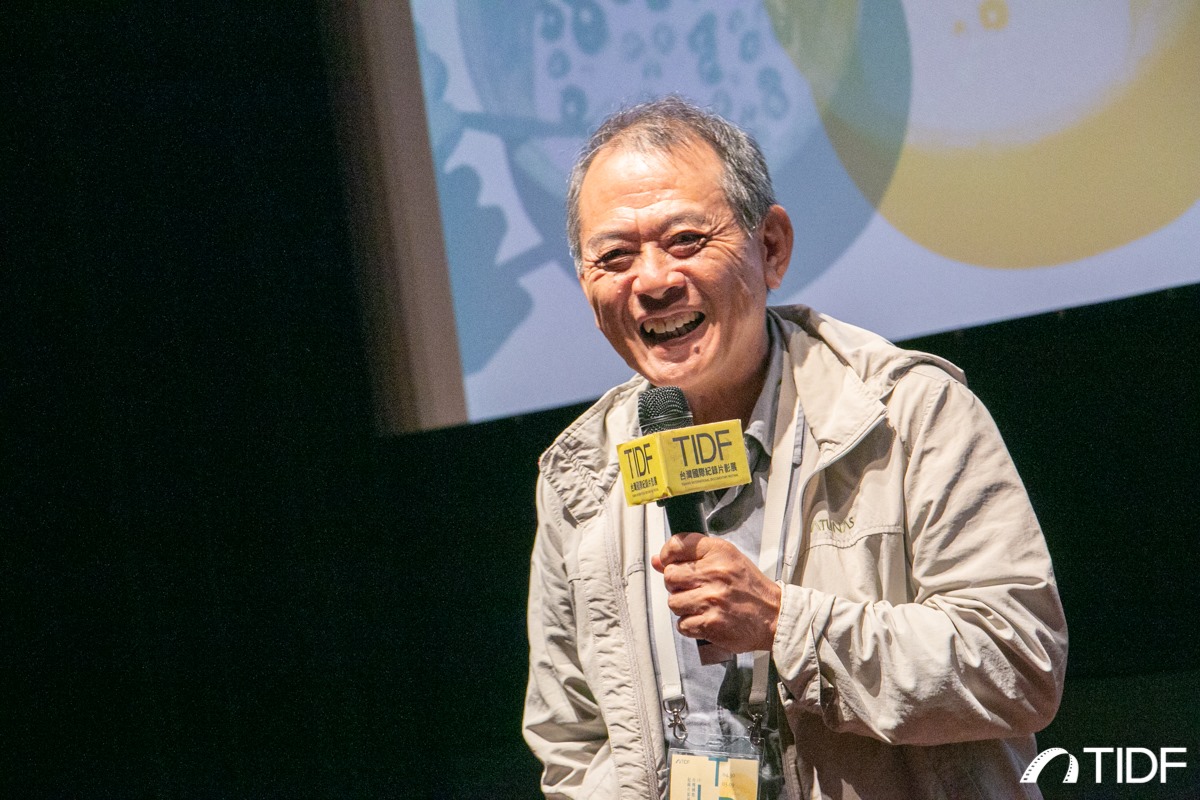

Interview with bauki angaw, for 2021 TIDF 'Taiwan Spectrum'

2021/08/06 18:00

As a photographer, why did you choose to explore your identity and the history of the Kavalan People through documentary filmmaking and completed The Kavalan: Past and Present?

I liked photography when I was in high school, but I didn’t have the money to buy my own camera until I began to work. By chance, I came to know JUAN I-jong and became his apprentice for a year. After my photography collection Outlanders was published, I went to Hualien in 1993 to do photography work with the local indigenous communities. During a visit to the community at Paterungan, the elders told me that there would be a harvest festival on August 18, and the Kavalan people from Yilan would also be there. I went to the festival with my camera, and I was surprised to see people from my clan there as well. This made me wonder if I had any connection with the Kavalan. I asked my father, and he said that we were quite possibly Kavalan.

Although this left a lasting mark in my memory, I didn’t think of making a documentary out of it at the time. Later on, when I was working at the Mennonite Christian Hospital in Hualien, I read in the paper that the Public Television Preparatory Committee was recruiting Indigenous trainees and I decided to apply for it. I told them I was a descendant of the Pingpu, a member of the Kavalan; they replied, 'There aren’t any Pingpu peoples left now, are there?' I was told to report for training, but I had no guarantees as to what would happen after I finished training. When I completed the training course, they said I could become a reporter covering Pingpu peoples around Taiwan, so I began travelling all about to find and document the Pingpu peoples.

So motion pictures became a part of your creative process only after you completed the Public Television Preparatory Committee’s Indigenous People’s Journalism Training Programme in 1994?

I didn’t have a clear notion at the time, I was merely trying to discover the different possibilities [between still and motion pictures]. In addition to technical aspects, our training covered theory as well, including subjects like politics, culture and indigenous history. Our lecturers included Icyang Parod, HU Tai-li, LEE Daw-ming, Paelabang Danapan and CHANG Chao-tang.

I made this documentary because I received funding from the United Daily News Cultural Foundation. I didn’t know how to write a project proposal, and the training programme didn’t cover this subject either, so I simply tried to write my family’s story as best as I could, and I managed to receive full funding [in 1997]. I was the director, and I went to a media studio to recruit a cameraman and an assistant, and so we began filming. We ended up with more than a hundred rolls of footage. I tried to do the editing myself, but because I had no real experience in documentary editing, I was crying while I edited the day before the review, and I ended up with an incredibly long rough cut. I went to the review with my eyes all red because I had no sleep at all, and the panel was extremely critical of it, but they offered no concrete editing suggestions, and I had trouble standing my ground. Ray JIING, who was the last of the panel to speak, said to the other panel members, 'I don’t share your perspective. For the first time in four centuries, the Pingpu peoples are telling their own story from their perspective, so we ought to assist him.'

The film documents the ‘dopuwan palilin’ ancestors’ rites of the Paterungan Kavalan. What do these rites mean for you? Why did you decide to document the ritual in full?

The ‘dopuwan palinin’ is a year-end ritual of the Kavalan meant to honour their ancestors, with strict rules forbidding the presence of non-family members. After spending many years with this family, they told me that I had to become their foster child if I wished to participate. I went through a simple ceremony to become their foster son right before my first ‘dopuwan palilin’, and thus I took part in the rites for several years in a row. When my foster parents passed away, I went to their funerals as their foster son.

I first rented a place to live in Paterungan in 1993. Later on, as I became more and more familiar with them, I would stay in their place. During my time there, religious rituals were what symbolized the Kavalan the most, so I’d film every ritual held there. In particular, I was documenting the priests, their rites, and how they lived their lives; I used my camera to document how the priests embodied Kavalan culture and it reinforced the way I identified with the Kavalan; if I didn’t have such exposure to the priests and their rites, my identity might have been shaped in some other way. These rites were very clearly defined, with strict rules governing times, taboos, songs, plants and ritual tools, offerings, and ritual directions. The priests and their rites bore a lasting impression on me.

Was this how you began to learn about the Kavalan community?

After I learned about my identity in 1993, I began to wonder: why didn’t anyone talk about our people? I only began to know more about our people after I went to Paterungan and other indigenous villages on the east coast. Around this time, the government of Yilan County was preparing a new edition of the official county history, and I would often go to their seminars. Government officials and historians used to say that the Kavalan had long been ‘Sinicized’ and were therefore not considered an Indigenous people. In reality, ‘Sinicized’ meant ‘disappeared’.

The official explanation, that we were a ‘Sinicized’ people who had ‘disappeared’ from the record, was set down by Japanese scholars during Japanese rule, and this silently shaped the prevailing stereotypes among academic circles later on in Taiwan. In fact, when the Kavalan began their reclamation movement to demand official recognition in 1987, the Kavalan language was still being spoken, each indigenous village still had their own rites, and there was still a distinctive tribal culture, yet even up to the mid-1990s, the prevailing stereotype was still a major hurdle. Not wanting to be deterred, I devoted all my effort to documenting Kavalan culture, rituals and daily life, and published the photography and essay collection The Kavalan - the indelible dignity and memory in 1999, so that the government and society at large could see for their own eyes the real Kavalan. These are the Kavalan people, so why do you find it so difficult to acknowledge this fact?

Why did you shift your focus from just the Kavalan to other Pingpu peoples as well?

This was largely because of my job at the Public Television Preparatory Committee. I believe that other Pingpu peoples have seen the same fate as the Kavalan, and in the documentary I put in my name card and a map showing the distribution of all of the Pingpu communities as a way of showing our connections. When I finished shooting The Kavalan: Past and Present, I bought a video camera with the money I had left [a Sony DCR-VX1000, the company’s first DV camcorder, first launched in 1995]. I also had a company-issued video camera, so with these two machines, I began documenting the Makatao, Ketagalan, Taokas, Pazih, and Siraya.

On February 27th, 2001, we held a public hearing at the Legislative Yuan to discuss official recognition for the Pingpu peoples. I served as the main contact, travelling all across Taiwan with several Indigenous elders to ask the communities to send representatives to the hearing. At the time I was in my third year of graduate studies in documentary filmmaking at Tainan National University of the Arts [bauki angaw enrolled in 1998 after leaving his job at PTS and graduated in 2001]. About Indigenous groups took part in the hearing, including the Kavalan, showing that there were peoples that had been mistakenly thought of as Sinicized and disappeared, that we are Indigenous peoples seeking governmental recognition. The hearing was a highly significant one, its impact reverberating across the media, and it led to a revision of policies from the central government.

With your many years of experience in documentary filmmaking, do you still believe that films can serve as a catalyst for indigenous rights?

I used to think that filmmaking wouldn’t have much of an impact, but now it might bear some influence on some people. The government allows you to criticize them, but they simply never give you your rights, especially when Indigenous peoples are concerned. It’s always been like this, and it always will be: you can trash and yell at the government all you want, but after you’ve finished yelling, they just brush you off. They promise they’ll respect Pingpu rights during the presidential campaign, but once they get in office, nothing comes of it.

So why do you continue to make documentaries?

Much of my footage is still unedited. Documentaries can be used as plain and clear educational material. A Japanese scholar once complained of the dumbification of Japanese society, and you see the same here in Taiwan, where much is decided purely on ideological lines. Documentaries can serve an educational purpose for sure, or else what’s the point of holding a documentary film festival?

I’m teaching a course at the Hualien Tribal College on documenting indigenous plants. I ask my students to think of a plant that represents their community. How is the plant used, for example in rituals, in food and drink, or in architecture? Urban Indigenous youngsters might have no knowledge, but older generations do, so the young people need to do field research in their community to ask what significance the plant holds for them, and for their people. Plants serve as a means for them to learn about their community. Another example: When someone in our tribal village built a new house, I asked them if they’d conducted the 'temugaz' [house blessing ritual]. They’d never heard of such a thing, so I showed them two of my films, and they learned how the ritual should be held. As our culture has gradually died out, these documentaries can help the community relearn their traditions, and thus become a part of our cultural revitalization. We’ve lost so much in the past decade or two, but if we didn’t leave a record of things back then, all would have been definitely lost by now. Oral histories are not concrete enough, but visual images are solid, so you can learn simply by seeing with your eyes.

When the Indigenous News Magazine first broadcasted in 1995, the production team was keen to stress the programme’s 'Indigenous perspective' in the accompanying manifesto. Has that perspective changed today?

No, Indigenous perspectives will always be Indigenous perspectives. But what counts as an Indigenous perspective? If an Indigenous filmmaker simply picks up a camera, does that count as an Indigenous perspective? Yes, but it’s up for debate. For example, I once saw a documentary about the Truku people made by an Indigenous director, so of course it is an indigenous documentary that presents an Indigenous perspective. The documentary states that at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the Truku migrated from the Liwu River to Wanrong Township, but was this a forced or voluntary migration? Judging from the events after the Truku War [a Truku uprising against Japanese forces] in 1914, this was a forced migration, so why didn’t the film say it was forced? The film then said that by the 1980s, the Japanese were very fond of Truku textiles, yet this might be seen as a whitewashing of the Japanese colonial regime, since there was no mention of the massacre and forced migration of the Truku people. This also counts as an Indigenous perspective, only it’s one with a certain ideology behind it that you might not agree with, and this is something that must be put up for debate.

Can the increasing number of Indigenous filmmakers help with promoting an indigenous subjectivity and their voice?

I can only say that documentaries accumulate slowly. For example, I helped found the Lalaban Banana Fiber Craft Studio in the Paterungan tribal village, where there are more than a dozen documentaries covering subjects like rituals, history, arts and crafts, and cultural revitalization. Aside from conserving the tradition of banana fibre weaving, the workshop is also the only place in Taiwan where Kavalan culture is preserved and disseminated through documentary films. On the subject of banana weaving, we have several different edits of varying durations of 31, 17, 10, 4, and 1 minute in length. Which version we show depends on how much time the visitors have. Even for 50 or 60-minute films like The Kavalan: Past and Present, we have different versions as well. Films aren’t meant to be stored in a desk drawer, they’re meant to be seen, and having a place to show them allows visitors to have a more systematic introduction to the richness of Kavalan culture.

Date: May 8th, 2020

Place: King Tang Café, Hualien City

Interviewers: CHUNG Pei-hua, CHEN Wanling, Wood LIN

Editors: CHUNG Pei-hua, CHEN Wanling