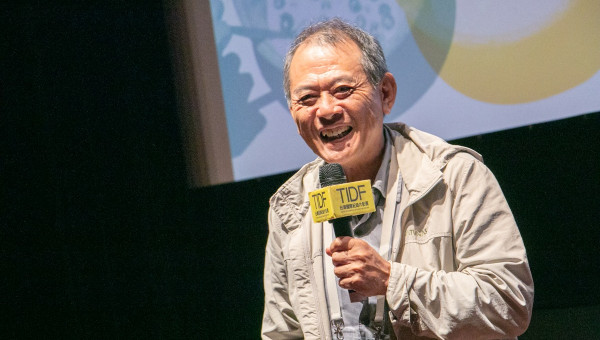

Interview with TAKAMINE Go for TIDF 2021

I understand that it was during your studies in Kyoto in the 1970s that you saw Jonas MEKAs’s Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania and you were strongly moved. What were your feelings at the time, and what were you thinking?

In 1970, I was sent from Okinawa to an art university in Kyoto as a government-sponsored foreign student. Okinawa at the time was under American rule and was not part of Japan. Activism supporting the reversion of Okinawa to mainland Japan was aflame. My parents expected me to become a doctor, even though they knew my grades were not good enough, and protested my becoming an artist. They were stuck in their thinking that “Being an artist equals life in poverty, eating potatoes and going barefoot.” Finding it hard to live in such a household, I left for Kyoto clutching my passport intending to run away from home. It was not exactly about aspiring to become an artist; I just wanted to make a fresh start.

However, the so-called “physical and mental gratification” from making brushstrokes didn’t interest me, and I ended up skipping class and just lazing about in my rented room. Maybe I believed in hesitation before formulating artistic expression.... With the swagger of being a painter who didn’t paint.... I sometimes used my 8mm camera to film Kyoto landscapes, but I never really felt at ease with either the so-called homeland of Japan or the hunk of its tradition as embodied in Kyoto. Around that time, I was infatuated with Japanese and American independent films by, for example, TAKABAYASHI Yoichi, Stan BRAKHAGE, and Andy WARHOL. I was particularly struck by Jonas MEKAS’s Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania.

Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania

Following up, tell us what it was about MEKAS that influenced you to embark on essay films about Okinawa in the road-movie style?

After I shifted the style of my expression from being “a painter who didn’t paint” to “viewing landscape through the 8mm camera,” I was still anguished, unable to decide on a concrete approach. Seeing MEKAS’s Reminiscences... pushed me into the “pond of cinema” with a plop. When I saw it for the first time on a 16mm film print with no Japanese subtitles, I knew very little about Lithuania or MEKAS, but the film to me seemed like a shuddering living creature, with its blindingly short shots and stop-motion techniques (it felt to me like shooting something with a gun) and the narration by MEKAS himself which was so calm. I became smitten with Reminiscences... as I watched it overlapping my own memories of my Ishigaki Island home. I later reinterpreted this “shuddering of cinema” by MEKAS into the concept “Cinema’s mabui (soul)” which became the keyword to my own filmmaking.

Only later did I hear about MEKAS’s fate in the former Soviet Union and under the Nazis, and how harsh circumstances took him from concentration camps to land in New York, USA. I’m sure I’ve seen this film over ten times by now. I’ll never forget how his mother was making pancakes in the garden in Lithuania when he returned home after 27 years, and the bashful faces of boys hanging out on the streets of New York.

Cinema to me was all about commercial movies until I first saw independent films, and so I thought it had nothing to do with me, because films were supposed to be made in the studio system. I called the 8mm films I sometimes made “Artistic Visuals” that were independent of the cinema industry, but then I learned that there was another convention called “Film Art” that stuck itself to filmmaking and I felt rather uncomfortable about that. But when I discovered that something like Reminiscences...—which was like “drinking water from the well of your homeland”—was cinema, this encouraged me, and I decided not to hesitate to also call my own 8mm films cinema.

I was strongly influenced by Reminiscences... and came to consider Jonas MEKAS my mentor. The ultimate lesson I learned from him was probably, “Just study however you like....” I returned to the Okinawa which I had supposedly forsaken and started filming it with my 8mm camera.

But I was at a loss to what it was I should “just study however I like....” Maybe I was at the age when you don’t want to articulate what you really like. I guess my shooting on 8mm film was the necessary step for me to determine “what” it was I liked.

I decided to film “the smell of death lingering in the landscape” of Okinawa.

Looking back on your decades-long filmmaking career, do you see any change in your thoughts towards this film? Did your meeting with Jonas MEKAS and travels with him to Okinawa lead you to any new viewpoints?

Okinawan Dream Show (1974) was a film I made influenced by Reminiscences..., but in all my subsequent films, I felt it was only respectful to MEKAS to depart from him.

In 1996, I met him in Okinawa for a TV program that was set up by a poet I knew in Tokyo. We drank awamori (an alcoholic beverage indigenous to Okinawa) profusely and recorded a conversation, but I hardly remember what we talked about. He sang Lithuanian songs loudly at our nightly drinking sessions. I paid tribute to him by singing Okinawan folk songs in punk mode. While walking along the Okinawan beach, he shot several frames of me without looking through the viewfinder of his Bolex 16mm camera. To this day, I have not seen the video of that TV program.

After they finished shooting the TV program, I continued to film him in Okinawa using my small digital camera and completed it as Private Images of Ryukyu: J.M. (1996). I compiled scenes with him, and after his departure, daily scenes without him. This film provided me with the occasion in 2006 for some of my films to be shown at Anthology Film Archives, the theater for independent films run by MEKAS himself. Anthology Film Archives is a theater specializing in independent films of which MEKAS is Director. His book of film criticism Movie Journal: The Rise of the New American Cinema, 1959-1971 became my mandatory reading. It was around that time that I learned that he was the guardian saint of independent film.

During our travels to Okinawa for the TV program, I showed some of my films to him who called them “camp films”—To this day, I don’t understand what he meant.

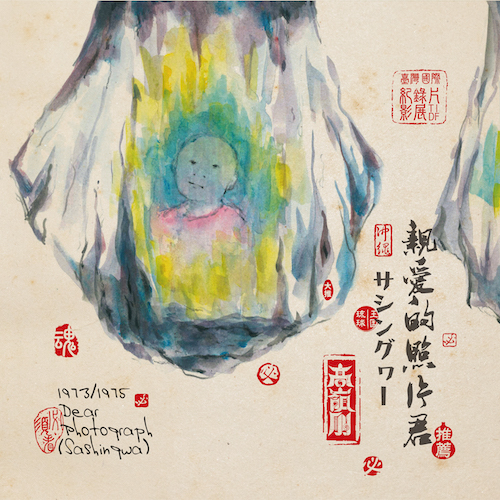

Dear Photograph (“Sashingwa,” 1973) is a “re-recording” of sorts, as you used your camera as if you were caressing the family photos one by one, so that the camera movement emphasized how photographs themselves are a record. At the time you made the film, were you aware that this approach included such an allusion to documentation?

When I shot this film in 1973, I had no intention of making a cinematic work, but just thought of it as a single concept film that was a twist on memory. The family recorded in the photographs is my own, but introducing my family was not the point—I was hoping to reproduce a certain “breath of spirituality” that formal group photos in general conjure.

I hear that Dear Photograph (1973) was made after your first art exhibition. Tell us why you decided to transition from painting to moving image at the time of its filming and production. Why did you use the affectionate Okinawan term “gwa” in the original title (“Sashingwa”)? How does the film connect to the idea of “re-recording family photographs that are already a record”? What does this film mean to you personally?

Dear Photograph is a record of recorded memory. I enlarged old black and white souvenir photographs I found at home to the size of a newspaper and then added color. “Sashingwa” is colloquial Okinawan language. Sashin means photos. Gwa is an affectionate term used for small lovable things. The most commonplace photo album in any household will take on special meaning if ever the norm ceases to be the norm.

If you allow me to go a bit more in detail on how the film was made.... In 1973, I put on an exhibition of hand-tinted photographs. It was around the time my interest shifted from gaining “gratification from drawing original paintings” to dealing with “the uncertainty of memory.” Perhaps there was also an influence from pop art, which often utilized ready-made materials. This film is a 8mm record of that photo exhibition. As I watched the colorized photos slowly fade in and out to the accompaniment of the singing of an Ishigaki Island relative, it felt less a “record of a photo exhibition” and more like I was “touching memory.” That’s why I gave it a title and completed it as a film.

So far, I’ve shown Dear Photograph in many different ways. I’ve used multiple projectors to show images all across a wall, projected it on garden trees in the middle of the night (you could see the images vaguely—my neighbors were surprised), projected it on white sand near breaking waves on a beach and had a favorite folk singer come sing live (it was as if the memories were being purified by the waves). The tinting of photographs reminds me of pictures of American soldiers in the windows of photo studios during the Vietnam War. The colors are like the candy from my childhood. I chose to fade in and out slowly, so that it won’t interfere with the viewers’ musing over memory. I didn’t tint the faces. The white faces remain as an afterimage that can’t be distinguished from the real image, leaving the impression that the people in the photos are staring back at us.

Following up on the last question, how did you name the film Okinawan Dream Show (1974)? It’s a road-movie film that goes about identifying the “stench of death” in townscapes, in the everyday, among the homeless, the soldiers, dead dogs, and other landscapes. How did using an 8mm camera to “stare at the landscape” influence your later films and what was your objective?

Through Okinawan Dream Show, I realized that this kind of documentation of landscape was not really about investigating reality, but almost like a memory of a dream. Especially with the graininess of 8mm film material, I felt like dream and reality were living together.

According to my production notes from the making of Okinawan Dream Show:

- Don’t go copying Jonas MEKAS’s Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania, just because he is mostly unknown in Okinawa. Aim for a film that embodies the kind of “Cinema’s mabui (soul)” that only cinema can capture. Copying MEKAS’s spirit is okay.

- Don’t think you’re a hotshot just because you imported something fashionable in Japan to Okinawa.

- Don’t believe cinema is privileged. (Be self-critical about the fact that holding a camera often makes you arrogant.)

- Don’t shoot in order to make a film, but start from observing daily images of Okinawa—Is the camera necessary? —Don’t rush to conclusions—Just never let go of your 8mm camera.

- Make sure your film is not just something you didn’t do.

- Don’t shoot, or don’t be persuaded to shoot, what would only serve as symbolic images that borrow from the Reversion to Mainland movement.

- Not a Japanese film—It’s a Ryukyu film—Films that can only be shot in Okinawa—Make sure to have style.

- Don’t consider your film subject as convenient fodder for your film.

- Don’t use Okinawa as film material. Films should not butter up to Okinawa.

- The “mabui (soul) that drifts around Okinawan land” is virtually the same as the “mabui (soul) of Cinema.”

- Cinema’s “mabui (soul)” settles well on the grains of 8mm film material, so don’t think of graininess as failure.

- Don’t be envious of professional-seeming 35mm.

- Don’t get caught up in heroic Play Cinema that just explains Okinawa politics—Don’t Play Art, pretending to make artsy fartsy films.

- It’s okay to debate fiercely with your staff (although it’s just the two of us, me and soundman Mr Tarugani) but never force dogmatic ideology onto each other.

- Don’t force your own personal experiences, generational experiences, regional experiences onto others.

- Don’t conclude that family and friends are uncinematic. Don’t underestimate the home movie.

- Decide only on a general direction when going off to shoot (on Mr Tarugani’s 750cc motorcycle)—Beware that if you pin-point your destination, the act of filming will be reduced to going through the motions to reach your objective.

- Try not to establish a center to your screen. Make viewers imagine all sides outside the frame.

- The smell of death in landscape—The “mabui (soul)” of the war dead from the Great War are still floating about, unresolved, amid the landscape of Okinawa. (Is there any way to resolve this? What are these mabui doing, and where?)

- The camera and sound recorder are tools to suck up the smell of the “mabui (soul)” that drifts in the landscape. Therefore, the basics are 20 minutes per scene, still frame, slow motion on less than 36 frames per second.

- To stare at the landscape—To be stared back by the landscape—Anything filmed through this “approach by waiting” will tend to be still, more or less—Make sure you don’t postpone your shooting plans, because people who remain still in a city landscape will easily be removed in the name of gentrification.

- Make sure you aren’t making artificial images like a security camera, in an effort to demonstrate that all landscapes are equal.

- Don’t shoot without looking through the viewfinder if it’s your way to “sidestep your subject.”

- Don’t pretend you’re friends, and then put away your things and leave right after the filming is done.

- Don’t overemphasize the cultural value of island songs, but use music mixed in the atmosphere of everyday life (like island songs from a taxi’s car radio or heard in a back alley.)

- Make sure you watch your rushes over and over, at least ten times. (It’s okay to drink awamori during the screenings.)

- Don’t be too strict on yourself and these notes about filmmaking, or you’ll get cramped.

I do think I’ve been able to, more or less, stay true to these points. In the end I edited 15 hours of footage (the projector has a variable speed control so I can only say “around” 15 hours) to three hours. I prepared sound to be played not from a sound track stuck on the film print, but from a separate cassette player, and then named the film Okinawan Dream Show. The “wan” of Okinawan commemorates the Okinawan people. “Dream Show” is about entertainment. My priority was how the words sounded together—After the filming—There was nothing pop or glam as the title suggested, but instead it turned out to be a “dream-tears-landscape film” with simple, modest, and lovable people.

For the screenings, I packed a 8mm projector and cassette player in a compact case, and pushing a converted baby carriage, went all around showing the film myself. (Stories galore: few audience, no audience, people using the movie for secret rendezvous, people demanding their money back because they thought they were going to see a 8mm porn film, danger / tragedy / regrets / distractions / group slumber)

In recent times, people seem to consider the film a nostalgic look back on everyday pictures of Okinawa from 45 years ago. That makes the filmmaker in me feel a bit queasy, because it sounds like I’m hiding my “filmic claws.” But never mind, because when I’d ask my favorite singer of island songs to come and do a 8mm screening with live singing, there’d always be a new Okinawan Dream Show and it’s lots of fun.

By no means does the Okinawan landscape belong to me alone. I’m talking about scenes from daily life and the amazing power of the island song singer....

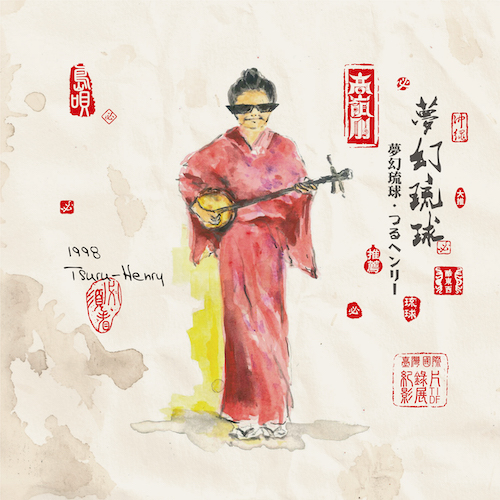

Your following films including Paradise View (1985), Untamagiru (1989), Tsuru-Henry (“Mugen Ryukyu: Tsuru Henri”) (1998), and Hengyoro (2016) are stories told through the fiction format. The historical backdrops of the stories vary but it is apparent that you take Okinawa’s reversion to Japan in the 1970s as an overarching theme. Why did you choose to tell stories about life in post-reversion Okinawa through elements that are imaginary, like folk stories and legends, magical beings, and fantasy?

There’s a ryūka (genre of Ryukyu songs and poems) by Okinawan island song singer KADEKARU Rinsho’s mother Ushi that goes: “Atara waga uchinaa / shinamun nu tatui / tutai turattai / kamini makachi” (Ah my Okinawa / Like merchandise / Grabbing and being grabbed / Leaving it to those higher up). It’s a poem bemoaning the dizzying yogawari (changing epochs) of Okinawa.

I don’t at all think that the humiliating rule under America were good times, but I felt oddly unsure about being told I was Japanese when Okinawa reverted to Japan on May 15, 1972. It was vexing to me that while the “master” changed from America to Japan, Okinawans could not become their own protagonist (literally, “master of civic society” in Japanese).

Scorning the unique Okinawan language in order to become Japan, rushing as if trying to catch up and overtake the mainland, rapidly turning Japanese—I had no intention of naively entrusting my film to the mood of the times and so set the historical period of my fiction films to the era before reversion to Japan.

About the beloved actors of my films—Actors of the Okinawan theater, singers of shima-uta island songs, karate artists, rock ‘n’ rollers—(not mentioning my Tokyo cast for now)—Even though I used Okinawan island songs immersed in the daily sounds of atmosphere, shima-uta singers are actually proficient entertainers in ways far beyond my imagination. And yet when you meet them, they are soh uchinanchu (true-to-life Okinawans) who are not at all unapproachable. Even though they are not film actors, they were already equipped with what the film needed at its base—the ability to express the Okinawan air—and so were able to fulfill their roles properly and methodically on set. Decisions about their acting were not made in complicity with me. If you use up your energy in detailed discussion before the shooting, the engine can stop running during the take. It’s true that agreeable discussion can lead to closer friendships, but on the other hand.... A film crew moving together in the same direction can bring about a “sense of gratification,” but sometimes the finished film on screen would feel slightly cramped. In my case, I stuck to my own until the film almost broke up. The actors were also probably acting on the very brink of their own breakdown, knowing that their truth was being sucked up into the film.

It’s commonly said but it’s a fact—it’s not easy to act out normalcy in a film.

According to my production notes during the making of the fiction films:

Paradise View (1985)

- Chiru (TOGAWA Jun) is Okinawan → Okinawan language (Japanese subtitles).

Ito (HOSONO Haruomi) is Japanese → Japanese.

* Japanese subtitles of the Okinawan language spoken by Okinawan actors

→ Also required in Okinawa.

- Loosening the bolts of the film’s framework → Overflowing into the landscape; Coming untied; Landscape intruding into the film. (There is no punchline to landscape).

- “Mabui (soul)”: According to local legend, “Mabui can sometimes fall from the body if the person encounters a strong shock. Normally the shaman would be asked to pick it up and restore it.”

- In Paradise View, mabui is interpreted to be “the spiritual core that allows a person to be human.”

- Paradise View is the story of a man whose mabui has been sucked away by the landscape, “a man who lost his soul; Mabuiless man”—The protagonist Reishu (KOBAYASHI Kaoru) is set up as someone who doesn’t notice he’s lost his mabui.

- Ant work: Mabuiless man Reishu’s hobby is “investigating the ecology of ants.”

(It doesn’t have to be ants → praying mantis, giant anteater, or baku (mythological chimera) are also okay.)

Tsuru Henry (1998)

- Photography: Even with a script, prepare a “cloth of cinema that is blank” and not yet colored

→ Place it on the shooting location for a while, and then start filming on top of it (it’s okay to film the local people’s everyday life, too).

- Editing: When it’s soaked in the smell of the land

→ Gingerly peel it off, making sure not to break it → Complete the film in a makeshift editing room rented on location.

- Retakes: Go back and do it again if it’s not “soaked enough.”

- Etc: Make sure to relax by holding drinking bouts → Partner with a liquor manufacturer and make sure there is no lack of awamori. Irabu (sea snake) soup meals every ten days.

- From the “mabui (soul)” of Paradise View to “machibui (chaos)” of Tsuru Henry.

- The keyword to Tsuru Henry: “machibui (chaos)” is a colloquial Okinawan term that reflects the chaotic state of Okinawan society. Each episode is restless and uneasy, with the storyline jumping ahead of itself, meandering into side alleys, and sometimes late. It’s as if the fish you caught had thrashed about in the sea and you are having a hard time untangling the fishing line—even while the boat is rocking—Oh how vexing that is....

- Radio program “Tsuru’s Wanderlust Island Song Dispatches” → Island songs of Tsuru (OSHIRO Misako).

- Narration should be in Yonabaru (a town in the south of Okinawa Island) dialect by Master TOMA Miezo.

- Burning James (MIYAGI Katsuma) → In the daily landscape, a boy who can’t die even if his upper body is on fire.

- Irregular “nest-in structures” such as the film-within-film and rensageki (a style of theater showing movies during the stage performance) (※Beware: a loss of narrative)

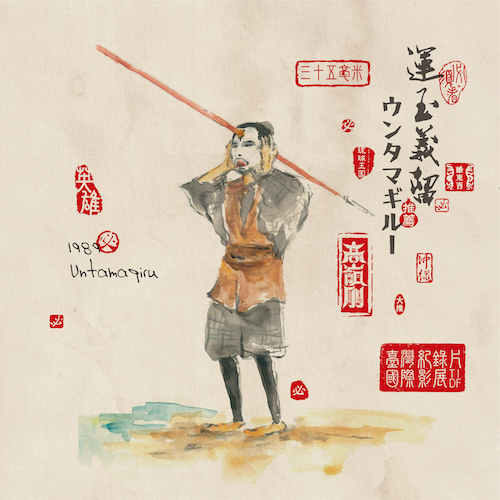

Untamagiru (1989)

- The spear in Untamagiru (KOBAYASHI Kaoru)’s head looks painful → The film should be languidly painful.

- Turned out to be slightly predictable because we mostly followed the script.

(※Managing to churn out even a film like this, I thought I could be another Federico FELLINI, but I guess I couldn’t.)

Hengyoro (2016)

- TAIRA Susumu, KITAMURA Saburo, KAWAMITSU Katsuhiro, OSHIRO Misako, OYADOMARI Chushin, ITOKAZU Ikumi, KONO Tomomi (Tokyo), YAMASHIRO Megumi, NISHIMURA Ayano, HANAI Reiko, UCHIDA Shusaku (Hyogo), ISHIKAWA Ryuichi

—I am very proud of the cast from Okinawa and beyond. (Okinawa has such amazing actors!)

Following up, what do you think is the connection between your filmography and these legends, folktales, and other fantastical elements?

Folktales and legends that have been revised and renewed repeatedly over time as they are passed from generation to generation become a treasure trove of stories from the land. I’ve tried to, rather forcibly, set up situations that convey where these folktales and legends find their place in today’s Okinawa. For example, take the folktale of “an old pig transforms into a human being and plays with other people...” If you consider this something that lies outside human understanding and just shoot it literally as a film, it can become a preposterous tale of fiction that is free from human logic. Bending or hiding historical fact is no good, but exaggeration and abbreviation go hand in hand with fiction.

So, are fiction films possible in Okinawa? The answer is yes. It’s very necessary. I’m not at all making films that just indulge in baring my soul or cling to the old Okinawa.

As long as “the core of Okinawa’s landscape” remained intact, I hoped that episodes that are preposterous or abbreviated could make movies more entertaining, because they would be free from being just vague reflections of reality.

Elements that heighten the film’s entertainment value: Gratifying landscape, people, story, words, and music are some, but there’s also “the author’s intention” that can’t be overlooked. Once the film is completed—There’d be subtle differences whether you see it on analogue or digital film, for work or pleasure, admission free or not, with or without subtitles, viewing environment, in a cinema, on the road, a familiar place, when you watch it, who to watch it with, how many times, from the beginning or not, whether you started watching from the middle and connected the storyline in your head, whether you watched it to the end, sound volume, on a big screen, on a TV, on a computer screen, on your smartphone.

In my case, as the author, I don’t watch it with an audience, I watch it after drinking beer, worry that the audience would eventually be disappointed even if they reacted to the early parts, always secretly checking if anyone is sleeping, boast how good the Okinawan actors are, regretfully recount the days of filming, remember that I was once called a filmmaker with “the guts of a flea and the zeal of a pit viper,” convinced that it’s a masterpiece when I watch it alone at home, discover that landscapes are always fresh to the eye:

Episodes don’t necessarily conform to the goal of the film.

One of the “cores to Okinawan landscape” for me is that tricky “chirudai (languor)” that floats about in a daily situation. The term chirudai tends to be used negatively in Okinawa to represent a state of un-productivity and laziness, but I consider the air that drifts about the land of Okinawa itself to be reverential and choose to call it “sacred languor.” But air cannot be captured on film, so I thought to express “chirudai (sacred languor)” by dealing sincerely with film locations that are yet untouched by the film, the storyline, island songs, and people.

In these films (as raised in the previous question), your narratives seem to get more complex, and you experiment with film style and methods of storytelling. How do you move your film ideas and productions forward, and what do you prioritize in the process?

In my case, there’s no question that I will always film in Okinawa. My filming of movie and Okinawan theater actors and the singers of island songs is in co-existence with the “mabui (soul)” that drifts about in the landscape. Cinema gives birth to cinema.

Critic NAKASATO Isao says your films constitute a unique “Takamine World.” They feature Okinawan language and geographic characteristics, and you’ve consistently cast the same artists of Okinawan traditional performing arts like Okinawan theater / stage and island song in your films. It’s as if the artists live within your films and have spent their lives inside this “Takamine World.” What is your take on the connection between the lives of the artists and your films?

When I ask someone to play a role as an actor in the films, I am borrowing from their real lives. This doesn’t mean representing Okinawa through social realism. Of course each individual lives their own daily reality, but what I mean is I am looking to cast people who are virtually breathing the same everyday air that the film requires. In this sense, I have succeeded almost perfectly. My biggest job on the set is to make sure we don’t destroy that special texture they embody.

In my view, there is absolutely no problem with repeating the cast in different films.

Some critics say Okinawan films should not be categorized as Japanese films. I believe your films and the land of Okinawa are in a mutual subject-object relationship. Tell us more in detail about your thoughts and your attachment to the theme of Okinawa.

When I came to Kyoto fifty years ago, I felt this was a foreign country. That, to this day, has not changed. It’s unlikely that unawares, my films over time become “Japanese films.”

My films don’t represent Okinawa. Okinawa will not allow that. I have no intention of becoming objective and composed. My hope is for my films to be like drowning in the Okinawan landscape.

I read your films to be, in a way, a search for a lost social position and identity, for a homeland to commit to. What do you think about this interpretation? Does such a homeland exist?

Familiar landscapes are gradually disappearing. Even if you feel you’ve grasped something guided by fading memories, “your landscape” just falls between your fingers. It seems there is no way to hold landscapes back. However much I long for the “voices or the voiceless voices” of the multiple mabui that drift amid the landscape, nothing can ensure that my wish will come true.

(※ In my next film Afa (tentative title) scheduled for 2022, I am envisioning a story about the “uprising of the mabuis.”)

There is often more than one version to your films. Some elements are used repeatedly. You use footage from Dear Photograph in Hengyoro, and you created a newly edited version of Paradise View for TIDF. Our understanding is that while the camera records a distinct moment, every new edit can change the storyline. What do these different versions and re-edits after time mean to you?

I believe that most of my films are in the middle of cinema creation. (There are various versions only because I keep overriding my own decisions. There is no guarantee the film will get better, but I keep trying.)

- Shooting is about confirming what can’t be done.

- I change my mind.

- I sometimes touch things up a bit when I play back memories.

- (Perhaps imprudently) talking about experimentation—Unraveling each episode from its parasitic attachment to narrative—Trying to recreate all my films so that they become one. Each episode is freed from the function they carried in the original film and shows another face—If I tire of that face, I just have to change it to another—Every episode backed up by good landscape can sustain that kind of rash treatment.

- When previewing the film to prepare for a new version, be precise in judging “which holes can be filled in and which can’t.”

As an Okinawan filmmaker, do you see remaining possibilities in exploring your core theme of “Okinawa’s reversion to Japan”?

I ponder on how, with each “changing epoch (yogawari),” the ruling authority can arbitrarily restructure the order of a society. Sometimes it happens “unawares” and sometimes openly against the people’s will.

At one point in the film Okinawan Chirudai (1978), I ask, “Is Okinawa Japan? When it loses ‘chirudai’ it will become Japan.”

When I once went to Okinawa to search for materials in researching your films, I encountered some of your paintings at OTA Kazuhito’s home. You appear painting a picture in a scene of KADEKARU Rinsho’s concert in Kadekaru Rinsho: Songs and Stories (1994). How do you decide which medium to use in your art? Do film, photography, and painting hold different meanings for you?

“Film” → indirect

- Each process in filmmaking, for example shooting, is a concrete task. Yet with each task, a battle is swirling in my head regarding the question of “the film’s intent—Does it work as a film?” Film tends to be a mental exercise—Ah, how frustrating.

“Painting” → direct

—Pre-production, during production

- Storyboard all shots in preparation for the shooting.

- Storyboards are supposed to be useful for the shooting, but sometimes I get carried away with for example reference photographs that depart from the film’s story, thus rendering them useless as guides for the production.

—During production, post-production

- Paint quickly without using your head too much → Live session with island song singers. (These paintings tend to be expressionistic, but not in the way of gaining “gratification of mind and body” that I hated as an art student.)

- Paint my favorite actors who kindly appeared in my films.

- Make sure not to cheekily invade the realm of real painters. (Don’t sidestep in from the cinema world.)

It is a great pity that you cannot join us for this special occasion. Would you have a message to Taiwan film fans and audiences?

I would like to express my deep appreciation to TIDF and the associated individuals who planned this retrospective, and everyone in the audience.

In both fiction and nonfiction, I’d like you to experience the “air” which is one of the key factors in understanding Okinawa. The air of Okinawan daily life is a rather abstract notion that may be hard to grasp, but it is something that the landscape, people, and island songs can transmit. I’d be pleased if you could feel its allure.